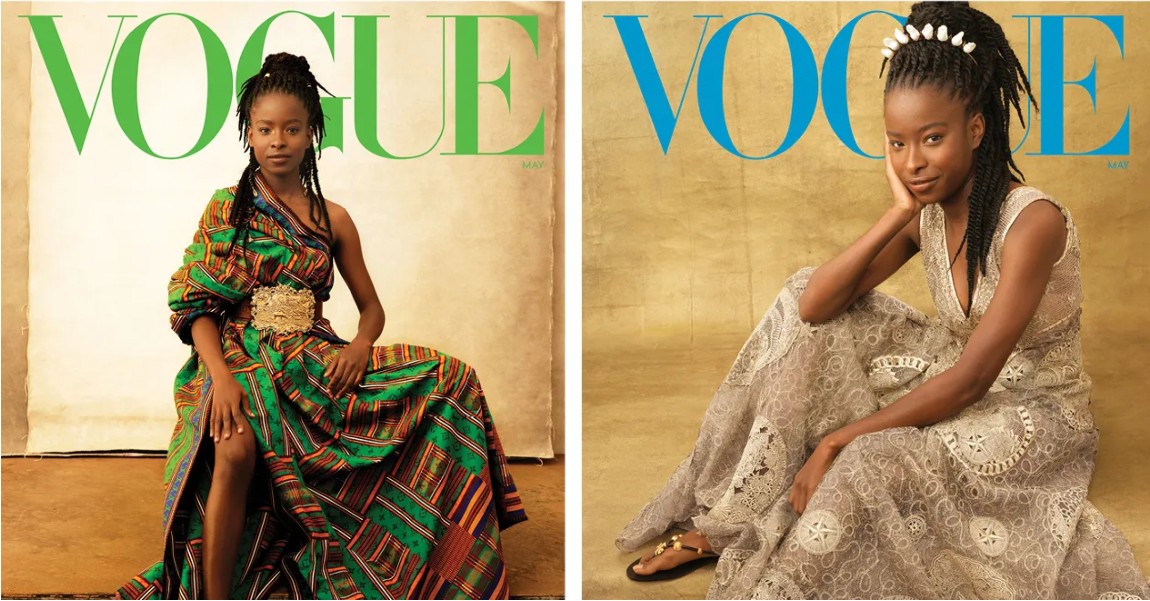

Deep in Amanda Gorman’s closet sits a doll that may or may not have stolen the facts of her reluctant owner’s life. A month after the 23-year-old poet eclipsed the transfer of power at President Biden’s inauguration with an energizing performance of her song of a nation, “The Hill We Climb,” she was thinking about an earlier, discomfiting booking—at the American Girl boutique at the Grove in Los Angeles. We were at a green space a stone’s throw from Gorman’s spot in L.A., a one-bedroom in an apartment building the color of sherbet. Reclining on blankets she spread over a manicured knoll, she tilted her head, birdlike, and groaned softly, “They might get angry at me for saying this.” The Mattel brand had invited Gorman to do a reading celebrating the arrival of Gabriela, the latest “Girl of the Year,” to expectant young customers. This was New Year’s Day, 2017, and Gorman was an 18-year-old freshman at Harvard, home on winter break, decompressing from the surprise of New England frost. At the time, Gorman had already been named Youth Poet Laureate of L.A. (the first one ever) and was a known and admired figure on the national spoken-word circuit. The night before the event, the American Girl team briefed her on the biography of the doll. It was like a horror movie—Peele-esque, we agreed after she told me the story. “Gabriela loves the arts and uses poetry to help find her voice so she can make a difference in her community,” the website for the defunct toy reads. Gorman loves the arts and uses poetry to help find her voice so she can make a difference in her community. Gabriela is brown-skinned with curly hair. Amanda is brown-skinned with natural hair. “She was a Black girl with a speech impediment!” said Gorman (referring to her own speech impairment), playfully clawing at the beautiful hive of twists atop her head, adding that her twin sister’s pet name is also, can you believe it, Gabby. Gorman did the reading anyway. American Girl told me that the doll was not inspired by Gorman’s life, and sent me a photo of Gorman, mid-performance, costumed in Gabriela’s exact outfit. “I felt like if I backed out of the event, I would have been failing the girls who would have this Black doll,” Gorman said. The rest of the year, when advertisements for Gabriela crept into her view, or friends would text her excitedly that they had seen her doll, she would avert her gaze, thinking on the mad vinyl thing she had locked away out of sight at home.

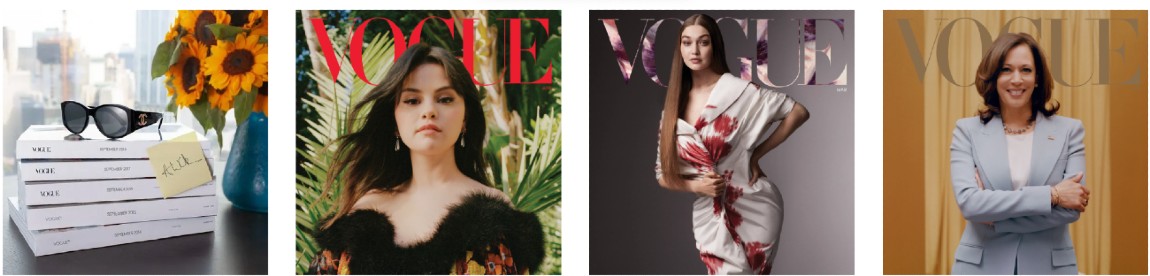

Gomez was born in Grand Prairie, Texas, a midsize town outside Dallas that once had a professional baseball team called the Airhogs, the kind of place where the top employers include Lockheed Martin and Walmart. Her parents were both 16 when she was born, in 1992. Gomez grew up in a neighborhood that was mainly Mexican-American, like her dad’s family. (Her mother, Mandy Teefey, who managed Gomez’s career until 2014, identifies as white.) She was named after Selena Quintanilla, whose music both her parents loved. Her mom let her splash around in the yard during rainstorms; her dad liked to watch Friday and Bad Boys with his cherubic baby girl. “It always smelled like fresh-cut grass,” Gomez remembers of her childhood in Texas. “We’d play outside for hours, and my nana and her friends would be sitting with their iced tea. It wasn’t a lot, but it was great.”

As a kid, Gomez was sensitive but fearless: A picture of her comforting another kid on the first day of pre-K made the local paper. (“Apparently I had just been like, ‘Peace!’ to my mom and walked right in,” she tells me.) She staged concerts in the living room and loved frilling herself up to compete in that particular Southern ritual—the beauty pageant. Gomez’s parents broke up when she was five, and Teefey mustered all her wherewithal to provide for her kid, working simultaneously at a Starbucks, a Dave & Buster’s, and a Podunk modeling agency. She ably shielded Gomez from the ever-present financial difficulties. “I remember always being reminded that people had less than we did,” Gomez says. “And we didn’t have much. But I felt like we did because my mom was always doing a hundred million things just to make me happy, and we volunteered at soup kitchens on Thanksgiving; we went through my closet for Goodwill.”

When she was 10, she was cast, alongside Demi Lovato, on Barney & Friends, which was conveniently shot in another Dallas suburb. The job didn’t feel like work: “You’re on set with a big purple dinosaur and dancing and having a great time,” she says, laughing. Three years after she wrapped her run on the show, she secured the role of Alex Russo on the Disney Channel show Wizards of Waverly Place and moved to Los Angeles with her mom. Gomez’s desire to oblige and enchant, inherent in any young performer, became enshrined as a mandate. Working for Disney turned Gomez’s life into a perpetual promotion, with her image quickly distributed through TV, music, movies, merchandise, live appearances, and cross-promotion of all of the above. “That was my job in a way—to be perfect,” she says. “You’re considered a figure kids look up to, and they take that seriously there.” Gomez’s Wizards character was sly and sardonic, lazy about both school and wizardry—that was the concept, by the way: a family of wizards running a West Village sandwich shop. But Alexandra Margarita Russo still radiated the essential Disney-girl quality: a spunky, unselfconscious precocity and confidence.

It became part of Gomez’s job to maintain that aura even as, simultaneously, the tabloid media began treating her as an object of interest. She was 15 when paparazzi began showing up on set. Her onscreen brothers, David Henrie and Jake Austin, felt protective of her. “We were all new to this, and they wanted to say things to the paparazzi, but you can’t, because that’s exactly what the paparazzi want,” Gomez says. “I remember going to the beach with some family members who were visiting, and we saw, far away, grown men with cameras—taking pictures of a 15-year-old in her swimsuit. That is a violating feeling.”

I ask Gomez whether she was aware of how invasive this situation was as it was happening, or if she brushed it off in the moment. “I think I spent so many years just trying to say the right thing to people for the sake of keeping myself sane,” she says. By dint of her personality, as well as the fact that she was a young woman in the spotlight, she had to be unconditionally grateful, composed, sparkling. “I’m just such a people-pleaser,” she adds.

Gomez is jet-lagged. She woke up at 4 a.m. and couldn’t go back to sleep. The room is warm, and the afternoon is becoming opaque, and the superstar in front of me is giving off a soft, bruised quality. I find myself, as many fans and casual observers of Gomez have found themselves, wanting to protect her, to make her happy, to cheer her up. Gomez is so invested in preserving a sense of normalcy that she swallows, in most moments, the strange side effects of having been on camera for two-thirds of her life. It’s a lifestyle that both exposes and insulates: Gomez seems acutely attuned to cruelty in all its forms, emotional and political, and also stunned by it every time. What’s most unusual about her—what distinguishes her from other celebrities in her echelon—is the way she’s grown softer, rather than harder, as she’s gotten older. The confidence came first; then came the confidence to let it drop.

In between, though, there was a non-negligible amount of chaos. At 18, when she was still filming Wizards, Gomez entered a serious relationship with a teen heartthrob, an entanglement whose off-and-on ups-and-downs were dissected constantly and voraciously until it ended in 2018. She was also releasing music—three albums before she was 20—with the pop-rock-lite band Selena Gomez & the Scene. In early 2014, in the middle of an international tour for her first solo album, Stars Dance, Gomez checked herself into a rehab facility. She was burned out and depressed, she tells me. She realized that she couldn’t understand the problem or work through it without help.

Gomez had also been diagnosed with lupus, a chronic autoimmune disorder that, in her case, was severe enough to require chemotherapy and send her to the ICU for two weeks. Eventually she needed a kidney transplant, which caused one of her arteries to break; a six-hour emergency surgery followed. Gomez woke up with two significant scars—one on her abdomen and the other on her thigh, where the surgeon had removed a vein—and the jarring news that she had, for some time there, been fairly close to the edge.

Throughout this, Gomez continued to work: acting in movies, routinely going platinum with her music, producing projects like Netflix’s controversial hit 13 Reasons Why. But she also retreated to treatment centers for two more prolonged stays, in 2016 and 2018. “I knew I couldn’t go on unless I learned to listen to my body and mind when I really needed help,” she says. She still has a hard time with late-night anxiety: the kind where you forget how to sleep and start thinking about what you want, what you have to do to get there. “And then I start thinking about my personal life, and I’m like, ‘What am I doing with my life?’ and it becomes this spiral.” She’s become a staunch proponent of dialectical behavior therapy, and she feels proud when the Selenators, as her fans call themselves, talk openly about finding help with mental-health struggles. She viewed her recent diagnosis of bipolar disorder as an important step to managing her life more soundly. “Once the information was there, it was less scary,” she says.

Gomez maintains steadiness in part by avoiding social media. “I woke up one morning and looked at Instagram, like every other person, and I was done,” she tells me. “I was tired of reading horrible things. I was tired of seeing other people’s lives. After that decision, it was instant freedom. My life in front of me was my life, and I was present, and I could not have been more happy about it.” And on Valentine’s Day of 2019, she wrote the spare and graceful ballad “Lose You to Love Me” with her favored collaborators, the songwriters Justin Tranter and Julia Michaels. The song hit number one; women came up to Gomez and told her that it got them through their divorces. Like you, probably, I’ve heard “Lose You to Love Me” several thousand times, and I still hold my breath a little at the tenderness in the melody, at the way Gomez offers a story of mutual culpability and weakness with a kind of grace that gives her the final word. “Once I stopped, and accepted my vulnerability, and decided to share my story with people—that’s when I felt release,” she says.

One of the side effects of having become so famous so early is the worry that people mainly know you for having become so famous so early. “I still live with this haunting feeling that people still view me as this Disney girl,” Gomez tells me. It’s partly a matter of her face, which remains stubbornly youthful: Even when she’s going full bombshell, you can still imagine her cheeks surrounded by flowers and cartoon hearts. Also, I suggest, her essential Selena Gomez–ness, the way she transmits her selfhood as readily and simply as a lamp gives off light, was there from the beginning. A person can’t rewrite the fundamental nature of her charm.

Over the phone, Steve Martin, her costar on Only Murders in the Building, tells me, “You get a list of names, you know, you’re thinking, Sure, they’d be good, they’d be good, and then they say, ‘What about Selena Gomez?’ and it’s just—yes, of course. There was no question except ‘Can we get her?’ We knew she would enhance the show in so many ways, the number one being talent.” Martin had never seen Gomez on the Disney Channel. “Her performance is rich and adult,” he says. “She’s learned to underplay when necessary. Marty and I are pretty manic, and she’s this solid, solid rock foundation. She’s nicely, intensely low-key.” When Gomez is on set, Martin says, there is no sense of her stardom. “She’s just working. And Marty and I joke around constantly, and we weren’t sure if she’d be game for it. But now we think of ourselves as the Three Musketeers.”

Revelación was produced by Tainy, one of the reggaeton masterminds behind Bad Bunny’s debut album and the Cardi B juggernaut “I Like It.” He was inspired, Tainy tells me, by Gomez’s readiness to work in another language. “It’s a huge task. It’s not easy; it takes courage. And she sounds amazing.” Revelación melds the percussion patterns and the instinctual pulse of Latin music with strings and piano, all beneath the forthright melodies that have become Gomez’s signature. “She has this tone that’s so distinctive,” Tainy says. “She can hit high notes if she wants to, she can explode in a chorus, but there’s this softness. It’s angelic. You want to leave space around her vocal. What I’ll say is, a lot of artists generate emotion through power—what’s different about Selena is that she generates emotion through subtlety.”

“The project is really an homage to my heritage,” Gomez says. Thanks to her paternal grandparents, whom she still—pre-pandemic, at least—visits in Texas frequently, she was fluent in Spanish as a child, but she lost the language after she started going to school. (Before each recording session for Revelación, she did an hour with a Spanish coach and an hour with a vocal coach. “It’s easier for me to sing in Spanish than to speak it,” she says.) Gomez—often implicitly figured, along with her Disney peers Lovato and Vanessa Hudgens, as part of a vanguard of Obama-era “post-racial” young stars—has been delving more consciously into the question of what it means for her to be Mexican-American. “A lot of my fan base is Latin, and I’ve been telling them this album was going to happen for years. But the fact that it’s coming out during this specific time is really cool,” she says.